Early History Of Water Island 1672 – 1900

The following chronology is loosely drawn from a report written by David Knight (Virgin Islands Historical and Genealogical Resource Center), “Into the Light – An Enigmatic History of Water Island in the Danish West Indies, 1672-1917”. Information below is referenced to the page on which it appears in the David Knight publication; the authors of this site have taken the liberty of interjecting additional information.

We highly recommend that interested readers obtain a copy of “Into the Light”. The book is full of rich details about the early Water Island residents and the relationship between Water Island and St. Thomas. David Knight is an accomplished researcher and author.

The First Occupants

It is not until July of 1686 that any reference to Water Island can be found in any of the Danish colony’s journals. On that occasion, a hunting and fishing trip was undertaken by a small party reporting that the bays were found to be full of pelicans, flamingoes, ducks and other fowl. The party encountered numerous wild bucks and goats, a few wild cows, bulls and calves. It was later reported that the green Iguana and Red-footed Tortoise were vestiges of past stocking by the former Amerindian (indigenous people of the Caribbean) occupants. ((page 3))

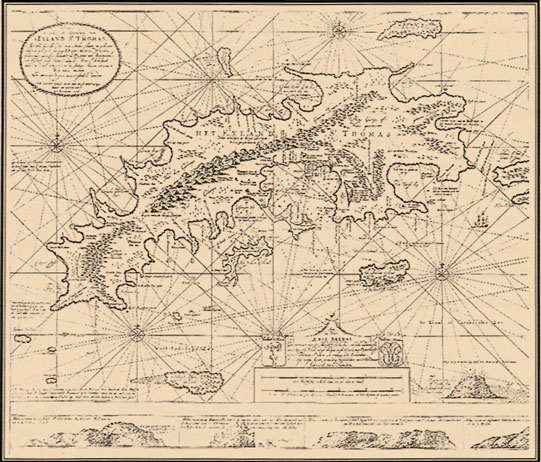

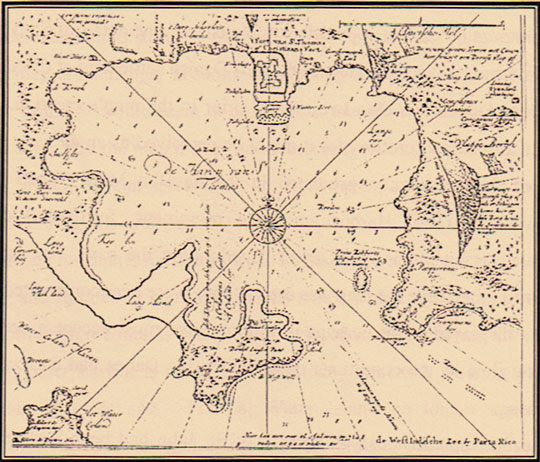

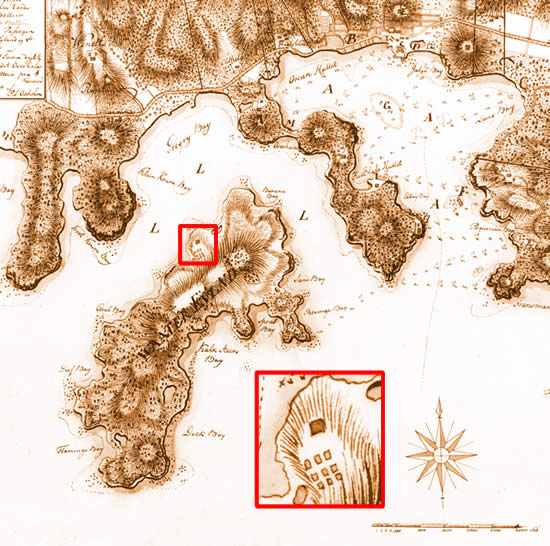

It is not until 1718 that the first documentary evidence of human occupation on Water Island is found. The source is a non-sanctioned map drawn by Simon de Bon Maison, a local planter and professional overseer. Several of the maps referred to as the 1719 van Keulen map of St. Thomas are shown below along with the first known map of Water Island. ((page 17-19))

On the map you will see “Water Island Haven” boldly scrawled, Grigri bay (a place where great ships and barques can anchor), the Flamingo Pond bay (known for its abundance of waterfowl), the Grape (Druif) bay (named for the edible sea grapes which can be found along the beaches), Sprat Bay (so called for its enormous schools of bait fish found in the coves), and the house and bay noted as belonging to Albert de Ruyter. ((page 21)).

The de Ruyter name appeared in the annual St. Thomas tax records in 1718-1719 indicating that he ‘bought a place that was burned down by Willem Bretz heirs’. ((page 22))

We are left to only speculate whether it was de Ruyter or Bretz who was the first occupant of Water Island under Danish rule. ((page 23))

Further examination of the Danish West Indies tax rolls permit calculation that Jan Cramieu Senior took up an unmeasured parcel on Water Island in 1717. ((page 23)) Later it is recorded that in or about 1723, Cramieu took over the Water Island property once owned by de Ruyter. ((page 30)) Again, the records provide no clear indication as to the first occupants of Water Island; Bretz, Cramieu or de Ruyter.

On 4 May 1733, the Cramieu heirs were given permission to liquidate Water Island. ((page 32)) No records of the sale can be found, but on the 1933/34 tax rolls it is shown that ‘Elias Baili resides on a piece of land on Water Island which according to records should belong to Crommelin. ((page 33)) So another twist of ownership.

In 1737, tax accountings show Crommelin as owning a 650’ wide cotton plantation in Frenchman’s Bay St. Thomas. It is surmised that Sprat Point, Water Island had been established by Crommelin sometime prior to 1734 as an appendage to the Frenchman’s Bay plantation. ((page 34)) In 1737, it is noted that Crommelin had fifteen enslaved laborers and one hired overseer present on Water Island. ((page 34))

Water Island appears in the Danish West Indies Company’s ‘Land Lists’ for the last time in 1740. Once dropped from the record, the island does not reemerge into the archival records for another twenty-nine years. Of note though, on 29 July 1740, records show that a boat from Water Island consigned to Crommelin arrived with two bundles of cotton. ((page 35))

In 1754, the Danish High Court rules that Water Island administration reverts to the Danish Crown. ((page 42))

In 1769, St. Thomas tax records indicate that Jean Renaux(sic), free Mulatto, is the owner of a near lying island called Water Island and is reported to own 18 slaves. ((page 44))

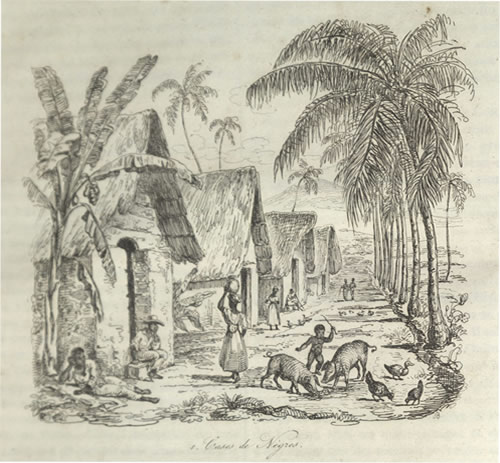

The 1776 detail map of Water Island by Peter Oxholm (shown below) ((page 46)) shows situated in the northeast terminus overlooking ‘Gregry Bay’ stands the Renaud estate residence and the houses of the enslaved laborers a short distance down the slope to the south. ((page 47))

Renaud prospered, began to pay yearly ground tax and by 1774 had thirty-one slaves. By 1786, the number of slaves has reached a pinnacle of sixty including newly imported Africans. Renaud died sometime in or about 1792 with forty-two enslaved workers on Water Island. ((page 45)) Renaud showed a degree of benevolence by granting freedom to some of his workers. ((page 51))

After resolving the Renaud will, Water Island became divided into two distinct land holdings. The northeastern half of the island becoming the property of Renaud’s wife’s new husband, Peter Tameryn, and the southwestern half becoming the property of the children of Renaud’s sister. ((page 52)) No exact boundary between the holdings is available.

In 1803 Peter Tameryn, now the liaison between St. Thomas’s rapidly growing Free Colored community and the Danish colonial authorities, was the Captain of the Free Negro Corps and still half owner of Water Island. The other half was now owned (through inheritance) by Jean Regis Poirier, a Free Colored carpenter from Martinique ((page 56))

Estate Water Island and

Caroline’s Lyst Plantation

Peter Tameryn, Estate Water Island (1793-1806). Tameryn resided on Water Island from about 1803 until his death in 1806. In an 1805 survey, Tameryn had 29 enslaved individuals living in 17 ‘Negro Houses’. Tameryn previously had as many as sixty enslaved workers. The estate encompassed 60 acres. ((page 60))

After Peter Tameryn’s death in 1807, Captain Archibald Kerr purchased the Estate and held the property until 1818. ((page 66))

Captain Kerr sold Estate Water Island plantation in 1819 to Baron Lucas de Bretton Sr. and by the next year had renamed the plantation Caroline’s Lyst. De Bretton resided on the plantation as a gentleman farmer. ((page 74))

During the period 1828 to 1848, Caroline’s Lyst changed hands no less than five times. ((page 81))

Christian Eckardt purchased Caroline’s Lyst in 1828 and then sold the estate to Owen Brown in 1829. ((page 83))

Brown sold it to Cosmo Francovitch in 1831 who eventually sold it to James Hazzel. (Note: this is the same Hazzel who inherited the nearby Hurricane Hole estate-today known as Hassel Island). ((page 83))

Estate La Providence

Jean Regis Poirier, La Providence Estate (1799-1806). Named La Providence by Poirier, tax records indicate that by 1800 there were thirty six slaves on the property housed in 16 ‘Negro Houses’ on the 60 acre plantation. In 1804, the Poirier’s took up residence at La Providence. ((page 65))

Madam Poirier died in 1828 in bankruptcy. ((page 77))

During the period 1828 to 1848, La Providence changed hands four times. ((page 81))

After lengthy probate, Madam Poirier’s two sister’s, Marie Castaing and Catherine Duranto, became owners of La Providence. ((page 85))

In 1828, Eliza Braithwaite purchased La Providence and sold it in 1831 to Joseph Coupris.

After the plantation had diminished considerably, Jean Garcia purchased it in 1838. ((page 85))

(Of note: the Danish West Indian colonies now fell into the hands of the British in 1807 and lasted until 1815. It was in 1809 that the British built Fort Shiply on Hassel Island to monitor activities in St. Thomas Harbor as well as Gregorie Channel and Water Island.) ((Page 69))

New Detail Map of Water Island

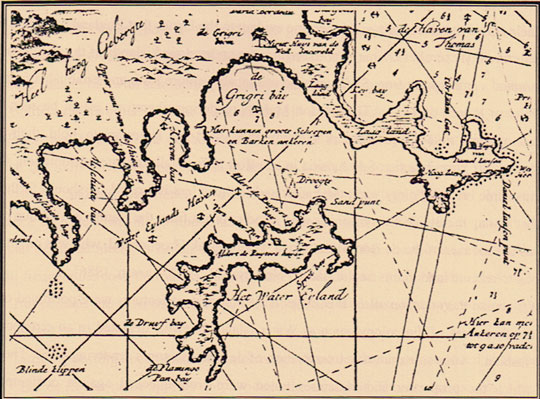

Not since the de Bon Maison map of 1718 had Water Island been mapped. The King’s Physician, Dr. Hornbeck, embarked on a four year project to map St. Thomas and its off-lying cays (including Water Island). With a span of 120 years from the de Bon Maison map, advancements in surveying, perspective drawing, and map making were startling. ((page 85))

The map below shows the detail of Water Island and the adjacent coast of St. Thomas. ((page 86))

The Hornbeck map shows the demarcation line between La Providence and Caroline’s Lyst, a road from Caroline’s Lyst to Limestone Beach, and the buildings of both plantations. ((page 86))

La Providence Plantation

On La Providence, Jean Garcia died in 1842 leaving the estate to his underage children. Fishing had become the primary activity on the plantation. Attorney Joseph Daniel represented the Garcia family (the name Daniel will pop up later as Daniel acquires the estate in 1850). ((page 89))

Caroline’s Lyst Plantation

On 23 March 1842, James Hazzel sold Caroline’s Lyst to Benjamin Barton, a sea captain. Upon Barton’s death in 1843 and after a long probate, the estate fell to his nearest living relations: Ann Quark and her husband John Quark of St. Thomas, and the underage children of Barton’s deceased sister (Mary Woods, John Woods, Eliza Woods, Isabella Woods, and Susanna Woods, all residents of the Swedish island of St. Bartholomew). ((page 92))

Upon Barton’s death, the tax rolls show no enslaved workers and no agricultural activity. Yet soon after his death, it was recorded that there was one free person and two privately owned slaves in residence on Caroline’s Lyst. By the 1846 census, the population has again increased to three men and four enslaved laborers. Two of the Free Persons were Augustine Rofilo and Jean Salvador both shown as ‘guards’.

Although the legally appointed guardian for all the Barton heirs, master blacksmith John Quark was in residence on St. Thomas. The 1846 census for Caroline’s Lyst was signed by Frenchman, Raimond Certain. The suggestion is that the heirs had leased Raimond Certain the estate sometime after Barton’s death.

But who were Augustin Rofilo and Jean Salvador? Why were they shown on the 1846 census as guards? When there was no agricultural activity ongoing, why were four enslaved laborers shown on the census? Perhaps the key to unlock these mysteries can be found in the 1850 census. The census notes that three of the seven occupants of Caroline’s Lyst were infected with leprosy. ((page 95)). Maybe guards were required!

Emancipation

Earlier in 1847, Danish King Christian VIII took the fist cautious steps toward total emancipation in the Danish West Indies. He proclaimed that on 28 July 1847, all children born into bondage would be considered as free and that all remaining unfree in the colony would become emancipated after a twelve year preparatory period. This decree heightened the volatile climate since emancipation had been declared in the British West Indies thirteen years earlier. ((page 97))

On 2 July 1847, alarms rang out from many estates announcing the slaves had risen up in rebellion. On the morning of 3 July 1847, thousands of negroes had marched to the Frederiksted fort and demanded their freedom. By the end of the day, Governor-General von Scholten proclaimed freedom from the ramparts of the fort. ((page 98))

Caroline’s Lyst Estate

The property’s house was reported, in 1849, to have a calculated interior floor area of an astonishing 7,984 square feet. By contrast, La Providence had a 1,547 square feet which represents a typical rural residence.

Raimond Certain, a native of Bayon France, was in residence along with two other persons and the three persons previously noted as having leprosy. Eight to ten acres were in pasture with as many as eight head of cattle and an unspecified number of goats and sheep. ((page 100))

Cholera Epidemic on St Thomas

In December 1853, three fishermen from the Hull plantation on the north shore of St. Thomas gave aid to a sailing vessel that appeared to be drifting and in distress. Unbeknownst to the fisherman, the vessel was a plague ship which later infected the population of St. Thomas with the Asiatic Cholera. With emancipation and increased mobility across St. Thomas, it was this newly acquired freedom of movement that made the 1853 cholera epidemic nearly impossible to forestall the deep and long lasting impact on St Thomas. ((page 103))

Caroline’s Lyst Estate

Living on the property in 1855 with five acres either cultivated or in pasture was 54 year old F.L. Christophe along with his wife and two young children. The 1855 census showed Richard King from Tortola as the resident ‘caretaker’ of the estate. Yet another census in 1857 showed Manual Mair, who gave his title as ‘inspector’, was the only person living on the property. ((page 103/4))

La Providence Estate

In 1850, Attorney Joseph Daniel purchased La Providence from the heirs of the Garcia’s. Only seven fisherman were shown living on the property. By 1851, Daniel made a concerted effort to evict the fisherman and convert La Providence back into an active small scale livestock plantation. Daniel even had a front page notice in the 22 December issue of the St. Thomas Tidende newspaper forbidding fishing, shooting, cutting of wood and otherwise trespassing on Estate Providence, Water Island. ((page 104))

By 1858, pastureland reached a peak of twelve acres. Daniel lived on the estate with his wife, three children, and two nieces. ((104))

From 1860-1900, Water Island and its bays became the focus of much attention. While the United States would not purchase the Danish West Indies for many years, the United State, Germany, France, Russia and Danish militaries looked at St. Thomas and Water Island as potential sites for a naval base and coaling station. The possibility of developing Water Island for maritime purposes pleased no one more than Captain Joseph Daniel (master shipwright, maritime entrepreneur, and owner of La Providence). ((page 107))

By 1865, Daniel had methodically acquired all of Water Island. ((page 107))

Consolidating La Providence and Caroline’s Lyst

As previously noted, Joseph Daniel’s name was first encountered in 1841 when he signed the census for La Providence as ‘attorney for Garcia’. Joseph Daniel prospered and by 1859, owned a fleet of lighters and a ship repair and rigging yard. By 1859, he had purchased some of the Wood’s shares in Caroline’s Lyst and all of La Providence. He slowly acquired the remaining shares of Caroline’s Lyst. In 1865, Daniel became the first person since Jean Renaud (1769) to be the sole owner of Water Island. ((page 108))

Although Caroline’s Lyst and La Providence continued to be noted in tax rolls as two independent land holdings, after Joseph became the sole owner of Water Island the two properties were once again run as a single estate. The main activity on the island was grazing. ((page 110))

Caroline’s Lyst great house burned sometime prior to the spring of 1862. ((page 108)) Web Site Note: See Archeological Report for data on findings of burned building.

Cholera, Hurricane, Earthquakes, and Tsunamis

1866-1867

Cholera hit the islands again in 1866 with 860 deaths by the end of the year. ((page 110))

In October 1867, a violent hurricane passed directly over the islands leaving some 77 ships sunk in Charlotte Amalie harbor along with hundreds of lives lost. Then later, on November 18, 1867, two violent consecutive earthquakes rocked the entire Danish West Indies colony. If not enough, the quakes were soon followed by a series of tsunamis that swept inland destroying everything in its’ path. ((page 110))

Joseph Daniel’s shipping support business was devastated, but survived and was rebuilt again. ((page 112))

For a more detailed account of these tsunamis visit the University of Southern California Tsunami Research Group.

Importance of the Danish West Indies to the United States

During the American Civil War, the Danish West Indies neutral ports were utilized as supply junctions for both the North and the South. This caused a dilemma for Denmark as it had longstanding relations with both Northern and Southern ports. ((page 105))

After the war, President Abraham Lincoln and his Secretary of State, William Seward, recognized that gaining control over the Danish West Indies was far more prudent than allowing the islands to be used against them in a future war. In 1867, a Navy Vice Admiral was sent to St. Thomas to evaluate the importance of the port and its’ surrounding islands. In the Admirals report, Water Island was mentioned as one of the best places to establish a depot. ((page 106))

At the very moment that the 1867 earthquake struck, an American delegation was seated at Government House on St Croix preparing to finalize the purchase of the Danish West Indies (St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John—not Water Island) for $7.5M. The U.S. Congress later refused to ratify the treaty.

Another furious hurricane struck St. Thomas on 21 August 1871. Damages were reported to be far greater than the disastrous storm of 1867. The near total devastation of the St. Thomas maritime infrastructure in 1867 and again in 1871 mark an important turning point in the fortunes of St. Thomas. Massive black iron ships now replaced the wooden sailing ships. St. Thomas became a way station for the coal hungry ships filled with goods and passengers headed elsewhere. The future of St. Thomas now lay in its massive heaps of coal brought from Europe. ((page 115))

Captain Daniel died on 23 July 1878 and his wife died in 1884 leaving Water Island to the children. ((page 117))

Although commerce droned on at a diminished rate, the St. Thomas economic situation was clearly grim. Some members of the community saw little choice but to appeal to Denmark for support. Others felt that association with the United States was the only reasonable path to pursue. ((page 118))

On 4 January 1902, the year in which America took over the Panama Canal, President Theodore Roosevelt sent a treaty to Congress to acquire the Danish West Indies. Congress passed the transfer and sent it to the Danes for approval. This time, it was Danish legislature that killed the transfer. ((Page 118))

Of mounting concern was the growing foreign naval presence in and around St. Thomas. ((page 118))

Water Island Emerges – 1900 to 1917

On 4 February 1904, an intelligence report was prepared by the U.S. Consul to St. Thomas and sent to the Assistant Secretary of State in Washington. This report noted that representatives of the German Navy have leased a small island known as Water Island. Further, that German and Russian squadrons have spent much time in target practice in the Water Island adjacent bays. ((page 119))

The report further notes that Germany is exceedingly anxious to get permanent possession on Water Island. Lastly, the report stated that Water Island is regarded by many naval people as the most desirable place in all the West Indies for docks, coaling station and general naval rendezvous. ((page 119))

Documents confirm that the title of Water Island passed from the surviving heirs of Captain Joseph Daniel through a series of intermediate deals finally to The East Asiatic Company on 1 March 1911. ((page 121))

After The East Asiatic Company’s purchase of Water Island, all agricultural activity ceased. Despite all the talk of grand plans, no projects to develop Water Island were ever undertaken. ((page 122))

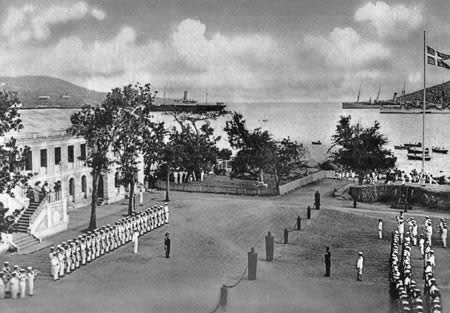

United States Purchases the Danish West Indies

On 17 January 1917, the U.S. ratified a treaty purchasing the islands for $25M. Transfer was achieved on 31 March 1917. ((page 126))

Water Island was NOT included in the purchase of the Virgin Islands as it was privately owned by The East Asiatic Company.